January 12, 2014

From early childhood to old age, a “rights discourse” dominates Americans’ sense of the world and our place in it. Governments around the globe, we are told, deny their citizens a long list of basic rights which we enjoy here. TV shows, movies, teachers, politicians, preachers, and pundits tell us again and again that what makes this country exceptional is our guaranteed access to rights and freedoms. But every now and then, experience complicates, even undermines, such assumptions.

On New Year’s Eve day, the management of the Mall of America prohibited the indigenous group Idle No More from holding a Round Dance. Days before the announced event, Mall management sent letters to the group’s organizers, asserting that “we prohibit all forms of protest, demonstration, and public debate.” The organizers’ insistence that this was not a “political protest” but a “healing ceremony” held no sway with Mall authorities. Their private security guards blocked entrance to the Mall to anyone carrying drums and arrested and handcuffed the event’s two primary organizers when, after a brief press conference, they left the outdoors sidewalk “free speech zone” and attempted to enter the Mall.

The local mass media showed little interest in reporting this action by Mall management. The press conference was sparsely attended. The story was not reported in either major daily newspaper nor by three of the Twin Cities’ four commercial television stations. The restriction of the right to free speech in such a heavily used space (the “21st Century Town Square,” some call it) appears to be of minimal concern to the local media.

There have been a number of occasions when this issue has been of great interest to labor activists, from the Mall of America to the downtown skyways. The local media turned a deaf ear to these activities, too, but reconsidering the incidents can offer us useful insights on the shutting down of Idle No More.

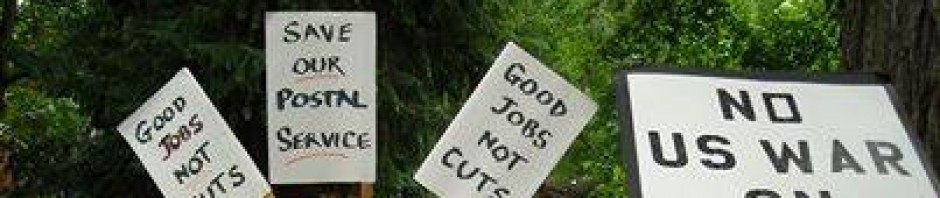

Postal Workers protest in 1996

In the fall of 1996 local postal workers became concerned with the news that a new post office/shop, “Postmark America,” was being opened at the Mall of America. Owned by the U.S. Postal Service, it would be privately managed and staffed. Despite postal management’s initial promises that the store would employ full-time unionized employees, they hired a complement of temporary employees through Manpower Incorporated. Since the store would offer the full-range of postal services, union activists saw this as a step towards the larger privatization of the U.S. Post Office. Its retail goods on offer, mostly toys and clothing, were made in China, Singapore, Jamaica, and Mexico, even the iconic stuffed “Patriot Bear,” whose costume included an American flag. When union activists expressed their intent to protest the opening of this store, they were informed by Mall management that they could not enter the property of the Mall itself.

This denial did not stop them, and they devised an ingenious strategy. A planning committee of local members of the American Postal Workers’ Union, the National Association of Letter Carriers, and the Postal Mailhandlers’ Union, together with experienced activists from other unions, commissioned sturdy union-made shopping bags with candy cane red stripes and a jolly Santa Claus figure. This Santa Claus said “No No No” rather than “Ho Ho Ho.” Inside the bags they placed a two-sided leaflet explaining why shoppers should be concerned about the privatization of the post office, the flooding of stores with non-union foreign-made goods, and the denial of free speech at the Mall of America. On the Sunday before Christmas 150 protestors rallied at a unionized motel near the Mall, took an allotment of ten bags apiece, and entered the Mall through different entrances. In some ten minutes they distributed 1500 bags – and political messages. The only media reportage of these events was in the Saint Paul Union Advocate.

Northwest Airlines workers protest in 1998

In the spring of 1998 Northwest Airlines workers, organized by the International Association of Machinists (mechanics, baggage handlers, and clerks), the Teamsters (flight attendants), and the Airline Pilots Association, felt that their negotiations with corporate management were reaching the breaking point. All had given concessions when NWA was struggling in the early 1990s. The airline had been profitable for several years and executives had been raking in big salaries and bonuses. But none of the unions had been able to negotiate a new contract which improved wage and benefit levels, let alone restored the cuts. In May, the unions began to meet together and threaten a workforce-wide strike. On the 22nd, activists sought to hold an “all unions” rally featuring Sheila Wellstone and Richard Trumka, then the AFL-CIO’s secretary-treasurer, as speakers.

This was when they discovered the limits on free speech, the right to assemble, and the right to protest. First, the Metropolitan Airport Commission denied them a permit to rally on airport property. Organizers suggested a move to nearby open space, the parking lot outside the Mall of America, the one with grass stubble and weeds. But after a couple of speakers, the reassembled crowd was informed by Mall security that they had to disperse. In one of the most cynical gestures participants had ever seen, security guards distributed two-sided leaflets: on one side was a legal explanation justifying the denial of free speech on private property, and on the other was a pastiche of coupons offering discounts at Mall stores. Only the Saint Paul Union Advocate and the Minneapolis Labor Review reported on these events.

IWW protest on Labor Day weekend 2008

The third labor movement experience suggests how the Mall management’s suppression of the rights to free speech, assembly, and protest could be extended even beyond the boundaries of its property. On theSunday of Labor Day weekend 2008, just before the opening of the Republican National Convention in Saint Paul, a feisty group of 50-60 labor activists assembled outdoors at the light rail stop on Franklin Avenue. They had come to celebrate the National Labor Relations Board’s upholding of a Mall of America Starbucks worker’s complaint that he had been illegally fired for trying to organize his fellow workers into the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The crowd, which was surrounded by a phalanx of masked police in ninja turtle garb, listened to speakers and proceeded to buy tickets and climb aboard a light rail train headed to the Mall. They announced their intent to accompany the individual worker in question as he reported for his first shift back at work at Starbucks in the Mall, pledging to buy lattes to celebrate his victory.

No local media reported on this story, either how it began or how it ended. The heavily armed police followed the labor activists onto the train, and when it arrived at the Mall stop, they blocked the doors and announced that no one would be allowed off, that everyone must return to the Franklin station. Not every passenger on board had been part of the labor demonstration, and some of them angrily asserted – to no avail – their right to shop. The train returned to Franklin Avenue, where the would-be shoppers, the would-be protestors, and the police all disembarked. The individual worker on his way back to work feared he might be discharged again, this time for being late for his shift. He wasn’t, but he would quit a few months later. Over the next week, RNC protestors in Saint Paul would see a lot of the ninja turtle clad cops as the struggle to exercise the rights to free speech, assembly, and protest would play out in the streets of the capitol city.

These three labor struggles – the postal workers, the airline workers, and the Starbucks workers – exposes the limits of the rights discourse which we have absorbed since we first entered a school room, turned on a television set, or opened a newspaper. Rather than confirming that the Bill of Rights guarantees all Americans sharply defined and uniformly recognized access to means of expression, the stories of these struggles suggest that such rights are circumscribed in fundamental ways, ways which shift the balance of power even further in favor of those who already wield power. Ironically, the privatization of space manifested in the Mall of America undermines activists’ ability to protest privatization itself. A long history of legal decisions has ranked property rights above free speech rights. In the past three decades, the ascendant neoliberal regime which shapes much of our economic, political, and cultural life has reduced even further the space where protestors can speak to their fellow citizens.

The mainstream media, once such an ardent advocate of free speech that firms and executives were active plaintiffs in precedent-setting legal cases, has become so beholden to capital that it now turns a blind eye to corporate repression of workers’ rights to free speech. Advertizing dollars count for more than eloquent speeches or well-developed ideas. Media corporations are themselves major employers who have adopted neoliberal labor policies – closing facilities, laying off workers, contracting out work, demanding concessions from unions at the bargaining table, or busting unions altogether. They are active agents in the undermining of workers’ rights themselves.

The repression of many kinds of protestors, from critics of the Republican National Convention to members of Idle No More, suggests that labor activists have faced similar challenges to those faced by other activists, challenges which often emanate from the same sectors of society, what the Occupy Movement called “the 1%.” Claiming free speech, assembly, and protest rights, from the Mall of America to the downtown skyways to the cities’ streets, is an item on the agendas of many movements and organizations. Crafting unity among them is the most promising path to make a “rights discourse” a reality in the 21st century United States.

(Photo at top courtesy of Rafael Morataya)

Our primary commenting system uses Facebook logins. If you wish to comment without having a Facebook account, please create an account on this site and log in first.